The detective novel is a very malleable form, capable of co-existing with most other genres. That’s because the detective figure, whether called by that name or not, is someone we enjoy spending time with. He does what we wish we could do: poke into holes, look behind curtains, tear off the mask to reveal that the monster was really just mean old Mr. Crump from down the road.

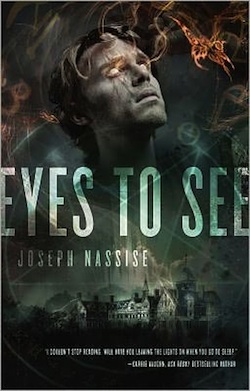

“Detective” is a job description, though. It’s like “bus driver” or “zumba instructor.” What draws us in is not the job, but the man who embodies it. That’s where Joe Nasisse’s novel Eyes to See really excels, because Jeremiah Hunt is a man with both a job and a mission.

In the great overall arch of the detective genre, the emotional involvement of the detective has reversed its importance. The original grand masters of the genre—Poe, who invented it, followed by Hammett and Chandler—presented detectives who were above the fray, observing and commenting on those involved in the mystery but keeping themselves out of it. They recognized the danger of involvement to both themselves and their career, and if they occasionally did succumb, it was with the full knowledge that their professional honor was at stake as well as their heart.

Contemporary detectives, for the most part, have no such worries. For one, they’re often not true “professional investigators,” with training from the police or military; they’re amateurs driven by personal demons or loss. Jeremiah Hunt fits this category perfectly: he’s a classics professor, someone for whom “investigation” is an abstract concept done in libraries or on computers. He’s self-taught, and his training has occurred on the job, with all the inherent dangers.

But most importantly, he’s driven by a personal mystery, the abduction of his daughter. There are few connections as tangible as that between parent and child, and it’s the intensity of that bond that explains the lengths to which Hunt goes to find her. In this cause, even self-mutilation is not too big a price to pay. Hunt gives up his normal “eyesight” in return for vision that might help him recover his daughter.

None of this is spoiler—it’s all there, right on the back of the book. But what the description doesn’t convey is the intensity of this father/daughter bond, and how well Nasisse uses it as the heart of the novel. There’s plenty of action and suspense, monsters and spooks, and the occasional wisecrack; but the thing that stuck with me after I read it was the reality of the emotions. I’m a parent, and I know I’d do what Hunt does, too. It’s not a matter of courage, or even something as trite as “love.” It’s a primal connection that binds the threads of this book together, and gives Eyes to See an impact greater than any mere “detective story.”

Alex Bledsoe is author of the Eddie LaCrosse novels (The Sword-Edged Blonde, Burn Me Deadly, and the forthcoming Dark Jenny), the novels of the Memphis vampires (Blood Groove and The Girls with Games of Blood) and the first Tufa novel, The Hum and the Shiver.

I’ve been hoping an audiobook for this would show up — any news on that front? (It took a bit for The Hum and the Shiver to get to audio, so sometimes such patience is rewarded.)